On a late afternoon walk, just before the sun sets you can still get a glint of them spread across the high desert. The scattered remains of the most epic battle ever fought on earth are there as a stoic reminder of a time when everything was at risk. The concerted effort of an entire nation, with the same dedication from a handful of allies, was on display as they joined to battle the greatest evil this planet has ever produced.

If you walk over to the source of the glint, and pick it up, you’ll be holding history in your hands. There are millions of .50 caliber shell casings laying on the open ground, drifted over by dirt, or stuck under sagebrush and prickly pear throughout the Gas Hills.

They are a not-so-gentle reminder of a time when Wyoming, the other 47 states, and the territories of Hawaii, Alaska, and the Philippines were joined in a death struggle with Imperial Japan, Fascist Italy, and Nazi Germany for control of all mankind.

No, there was no epic land or air battle fought in the isolation of Eastern Fremont and Western Natrona County, but tens of thousands of young men prepared for war there, and a few hundred died during the training.

Those dulled-by-the-sun .50 caliber shell casings came from the formidable Browning M2 machine gun, standard issue on B-17 Flying Fortresses, B-24 Liberators, and P-39 Airacobras.

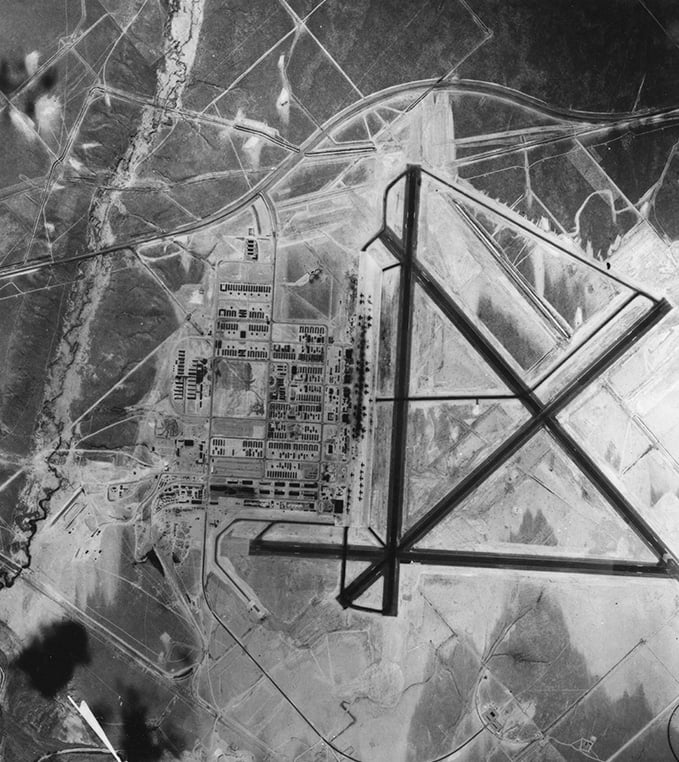

If a young pilot, bombardier, navigator, or gunner could transport themselves from the dark days of World War II to the modern Natrona County Municipal Airport, they would recognize many of the buildings and the overall layout of the facility.

The next time you drive to Casper and look to the left just as you slow from 70 mph to 55, you’ll see the modern transformation of the Casper airport from the original United States Army Air Force Base. (USAAF)

Casper was a training site for aircrews to perfect their skills before going into combat against the Japanese on any one of a hundred small islands or taking to the air to bomb the Third Reich from bases in England, Italy, and Libya.

We often refer to Wyoming’s second largest community as the “Windy City,” but it was that persistent, often annoying gale force wind that frequents Natrona County that had Army planners selecting Casper as the site of their main bomber training facility.

Training thousands of air crews costs a lot in housing, food, transportation, mechanical parts, and ammunition, but the largest cost by far was aviation fuel to get the big bombers and the P-39 to combat altitude. The supply lines for much of that fuel were short, with the aviation-grade gasoline produced in Casper.

Army engineers discovered the wind that whips consistently across Casper Mountain, and they decided to use it as means of generating extra lift, without using extra fuel. B-17s and B-24s took off from one of the three main runways, turned, and flew directly into that howling wind. Much like a kite leaps higher on a wind gust, the four-engine bombers did the same when they hit those strong headwinds.

It saved a lot of fuel in getting the planes to 30,000 feet for practice bombing runs, but it killed a lot of young men as well. Many of the 160 airmen who died in training at Casper were victims of mishandling the high wind during training flights.

The Casper Army Air Force Base was one of four major construction projects completed during World War II in Wyoming. The other three, the Heart Mountain Incarceration Camp, located between Powell and Cody, the forced home of 11,000 Japanese Americans wrongly imprisoned is the most famous.

Another prison facility, this one for German and Italian Prisoners of War was built at Douglas, and the Quartermaster Building, an addition to Fort F.E. Warren at Cheyenne, were the others.

Fort Warren changed to F.E. Warren Army Air Force Base during the war, and in 1948 became F. E. Warren Air Force Base, a mainstay of America’s missile defense system under the Strategic Air Command of the United States Air Force.

But in 1942, Casper AAF Base was just a wide patch of windswept sagebrush west of the suddenly booming oil town.

That all changed that summer.

In the brief period from the end of frost in the prairie soil until late August, 400 buildings sprang up. The base was active on September 1 with the arrival of 21 officers and 165 men in the 211th Army Air Force Training Unit.

For the next two-and-a-half years, the base bustled with activity.

The five main hangers of Natrona County Municipal Airport still operate after their erection in July and August, along with approximately 90 other surviving buildings that served as barracks, warehouses, machine shops, and service clubs for airmen, NCOs, and officers.

One of the more impressive features of the base were the four-mile-long runways. They were more than adequate for the initial arrival of B-17 crews in the fall of 1942, and their rival, the B-24 Liberators, the following spring.

“The base was built to accommodate 20,000 men to be trained. They would come out there, and they were trained to do the last of their training in the B-17s and the B-24s because they could go around the east end of the mountain and hit the zephyrs [west winds] to take them right up to the sky,” Joye (Marshall) Kading said in an archived, taped interview made in 2011.

Kading passed away in 2018 at 95-years of age, but in 1942 she was a 19-year-old stenographer turned secretary when the base began to take shape.

Cleona Joye Marshall, preferred her middle name and was born in Nebraska, but moved with her family to a dairy farm near Gillette, then on to Saratoga where she became aware of federally funded projects when her father, Clifford Dale Marshall worked for the depression era Civilian Conservation Corp. The family moved to Casper Mountain, the same area that would eventually vault heavy four-engine bombers into the sky in 1936, and she graduated from Natrona County High School four years later.

Kading was hired by the USAAF as a stenographer when construction began at the base. She took shorthand, typed, and created documents for the officers before eventually rising to the personal secretary for the base commander.

It was at this job that she met her future husband Frank Kading, a lieutenant in the quartermaster’s office. They were married soon before the war ended on June 21, 1945.

Kading was privy to information not available from other sources and had a treasure trove of memories from that brief 30-month lifespan of Wyoming’s only active Army Air Force training base in World War II.

Kading’s story was the story of the Casper Army Air Force Base, she was there from the inception to the closing in March of 1945.

Kading chronicled the construction of the base, then tallied daily missions, gunner’s scores, and the successful hitting or missing of targets in the Gas Hills with 100-pound bombs loaded with flour.

“The base was built to accommodate twenty thousand men to be trained. They would come out there, and they were trained to do the last of their training in the B-17s and the B-24s because they could go around the east end of the mountain and hit the zephyrs (west winds) to take them right up to the sky. The men who came out there were only trained probably, some of them, six weeks, some of them eight weeks, depending on where they had gotten their basic training,” Kading said. “When this war ended we had run through almost 18,000 men. That is quite an experience, it was a wonderful experience for a young boy, could not beat it. I’d do it all over again.”

The initial B-17 crews consisted of a pilot, co-pilot, bombardier (using the highly effective and top secret Norden Bomb Sight), a flight engineer, a radio man, and four gunners. Each of these men had to work in orchestrated unity to have even a semblance of a chance against the technological superiority of the Luftwaffe, or the piloting skills of the Japanese in their lightweight, incredibly maneuverable plywood-covered Zeros.

These were young men, with a few 17-year-old gunners, and “experienced” 21-year-old pilots and co-pilots about to enter the horror and carnage of high-altitude combat.

As kids, because that’s what these aircrews were, they relished their downtime off the base. Hunting pronghorn and mule deer on the plains west of the base, or on Casper Mountain, and fishing the North Platte, especially the “Miracle Mile” provided a welcome distraction from the terror that awaited them in sky combat with the ruthless German and Japanese pilots, and the incredibly effective destruction of the German 88mm anti-aircraft guns.

In December, 1942, the men in training were delighted to see Bob Hope and his traveling USO Show perform at the base. Many of the young men in the audience didn’t live another year after being dispatched to Bougainville, Guadalcanal, Sicily, or the United Kingdom. It was a war that we were not guaranteed to win.

While combat awaited as the true test of their flying, shooting, and overall skills, the training was no easy task.

”We probably lost maybe twenty planes with wrecks. The fellows hit something in the wind that they didn’t know how to handle, and they’d have a plane wreck and they were lost. A lot of our pilots were in training, and we had some of our planes wrecked in other states,” Kading said. “I would guess there were probably, maybe, twenty planes that were lost in all those trainings. The soldiers’ bodies were then shipped back home to their families.”

Those approximately 20 downed aircraft represented 160 men who died in training at Casper. Most of the crashes were directly after takeoff when the B-17s, B-24s, or P-39s were fully loaded with high-octane aviation fuel. There wasn’t much left of most of the wrecked aircraft aside from a few pieces of charred metal, and the sand of the high desert fused into glass from the heat of the incinerated wings and fuselage.

Training began with pre-flight checks, and the big war birds taking off on solo flights. Once the pilots and crew mastered that they trained in formation flying.

Crews assigned to the Pacific often flew solo missions or in smaller squadrons of just a few planes. But as examples the B-17s that bombed Dresden and the B-24s that destroyed Ploesti, Romania flew in combined squadrons of hundreds of four-engine bombers, with some raids having more than a thousand planes in the air at once.

A failed concept early in the war over Germany, France, and Belgium had B-17s flying in formation without fighter escorts. The nickname, “Flying Fortress” was thought to provide enough protection for the gunners to overlap fields of fire and protect the group as a whole. The Messerschmitt 109s and Focke Wolfe 190s had different ideas and ripped the bombers apart before long-range P-38s, P-47s, and P-51s were adapted to provide fighter support.

The P-39s at Casper were eventually brought into the training to simulate a fighter escort as training squadrons took to the skies with bomb bays loaded with 100-pound bombs filled with flour.

A target was marked in the sagebrush in the Gas Hills or on the slopes of the Rattlesnake Range and the lead bombardier, carefully targeted the bomb drop with a Norden Bombsight.

The flour exploded on impact, leaving a clear indicator for the photo-reconnaissance aircraft recording each training strike on film to spot.

There aren’t many remnants of these strikes aside from a few thin bands of rusted metal that once held the flour-filled bomb cylinders in place. The wind, snow, and rain have largely erased this bit of history.

The evidence that remains came as millions of spent .50 caliber cartridges rained down from the waist gunner, tail gunner, top turret gunner, nose gunner, and the ball turret gunner’s Browning M2 machine guns.

They shot at targets towed behind C-47s on cables several hundred yards long. It wasn’t easy to photograph a flapping sheet of canvas towed at 150 miles per hour, but when they landed, the training officer and the officers observing the machine gun fire in flight debriefed the crews and instructed them on their technique and effectiveness.

The training was intense, but the targets weren’t firing back with 20mm machine gun fire as the Luftwaffe would soon offer these young men.

Their stay in Casper was brief, but almost 20,000 young men trained at the facility until it closed in March of 1945.

What became of each teenager, and early 20-something that graduated from Casper is unknown, what is known are the sobering statistics from the war in Europe alone.

There were 40,000 American airmen killed in combat, another 18,000 were wounded. That’s the highest killed-to-wounded ratio of any American combat group in the war. You didn’t survive often when your aircraft took a direct hit from a German 88 or was riddled with 20mm machine gun fire.

If you were lucky enough to bail out or survive a crash landing as 6,000 airmen did, you spent the rest of the war in a German Prisoner of War Camp.

During the war, 18,482 B-24s were built, along with 12,731 B-17s and 9,584 P-39s.

A few carefully preserved relics survive.

The Casper Army Air Base Servicemen’s Club was decorated with murals painted by men training at the base. You can still view their work in the same building, now repurposed as the Wyoming Veterans Memorial Museum and those western zephyrs still blow.